Brexit and water law: Implications for the UK and Scotland

The recent heatwaves, and accompanying drought, have flagged up the importance of water policy – and water law – as we seek to manage scarcity in the face of climate change. Currently, water laws in UK jurisdictions implement a set of EU directives applying to water quality, water resource management and service standards (drinking water and waste water). Focussing mainly on the UK and Scotland, I consider Brexit’s potential impact on UK water policy currently covered by the EU Water Framework Directive (WFD), and the directives on drinking water quality and urban waste water treatment.

The Water Framework Directive

The WFD is an ‘umbrella’ linking several water directives ranging from flooding, to bathing waters, to priority substances, as well as water services. It is also a complex long-term planning instrument, requiring EU member states to set up river basin districts and produce river basin management plans, with programmes of measures, including for any transboundary basins. As such, it is an instrument for Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) which states around the globe have been committed to since the Johannesburg Summit in 2002.

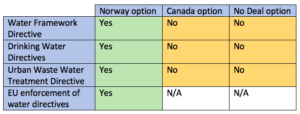

Whether the WFD (and other water directives) will continue to apply to the UK depends on the form of Brexit that emerges. A ‘Norway option’ scenario – where the UK would remain in the European Economic Area, the EU single market, and the EU customs union – would lead to significant policy stability: the WFD and most other water directives are included in the European Economic Area Agreement and Norway has implemented the WFD. Switzerland, which is not in the EEA, does not implement the WFD but does use some comparable approaches.

Under ‘Canada option’ or ‘No-deal’ Brexit scenarios, there would be more room for policy divergence. The UK Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan addresses water quantity and quality and specifically mentions meeting or exceeding the measures in the River Basin Management Plans (for England). Something like these plans would be required to meet the UK’s international commitments to IWRM, though would not need to comply with EU WFD timescales or other requirements.

Application of EU water directives under different Brexit scenarios

After Brexit, the Scottish government is committed to maintaining the environmental aquis, including water-related regulation. This commitment could lead to water policy divergence within the UK. However, the decision of the UK Supreme Court on the Continuity Bill will determine who will lead on environmental governance in Scotland in the short and medium term. But it is likely that river basin planning will continue in some form, now that it is well established.

The cross-border river basins between Scotland and England and Wales and England are already managed to reflect their different legislative and administrative arrangements, but the basins between Ireland and Northern Ireland are transboundary waters. Currently, both Ireland and the UK are required to ensure coordination and achievement of the WFD objectives. After Brexit, the EU will expect Ireland to ‘endeavour’ to do these things. Whilst existing cooperation is likely to continue, it is unlikely to be the highest priority for border arrangements in Ireland.

The WFD also requires states to achieve ‘good ecological status’ for surface waterbodies, unless stated exceptions apply. The meaning of ‘good’ and the whole classification system, as well as the obligation and its exceptions, are technically and legally complex and the science is iterative. As a result, the implementation of the WFD has led to significant resources deployed in water management and water science across the EU. The underpinning science will continue to develop, so even if the UK retains a commitment to ‘good status’, if it does not shadow the EU then the definition may no longer reflect emerging practice.

However, the 25 Year Plan suggested that, after Brexit, an appropriate target for English freshwaters is that 75% should be ‘close to their natural state’, rather than ‘good status’. Evidence to the House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee suggested that this was unambitious, although the English river basins are certainly not alone in failing to meet the WFD’s requirements.

Water Services: Drinking water and waste water

The Drinking Water Directives set mandatory technical requirements for water services. These requirements are based on World Health Organization guidelines, but are tailored to the EU and go beyond the WHO in some aspects. The technical standards are therefore the same throughout the UK. However, Scotland has always had separate water laws, and services were never divested and are now delivered by a public corporation. After Brexit, it is not clear whether drinking water standards would fall within ‘the environment’, or public health, or indeed food safety. But governance arrangements between the UK jurisdictions are still uncertain for all of these policy areas.

On wastewater, the Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive has been contentious across the EU, before and after enlargement. It required considerable capital expenditure to implement. When the Priority Substances Directive was under review, with proposals to extend the Annex to cover emerging pollutants such as pharmaceuticals, a well-publicised report in Nature suggested that the impact on the costs of wastewater treatment in the UK could be £30bn.

The political angst that resulted was partly responsible for placing the relevant pharmaceuticals on a ‘watch list’ for monitoring, rather than within the Annex. If watch list substances do make their way onto the Annex, and changes are introduced that require upgrading wastewater treatment plants, the UK might decide there is no need to continue to mirror EU standards in UK law. And whilst wastewater is a devolved function, chemicals regulation will need a UK-wide approach.

Enforcement of water law

Enforcement will also be an issue for post-Brexit water law, as it will be across other areas of environmental law. The House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee’s report noted that the UK Government is proposing a ‘green watchdog’ that will not have the enforcement powers currently held by the European Commission. Moreover, if the UK leaves the EU and the EEA, it is likely that water-law reporting, whether against the measures in the River Basin Management Plans or the standards in the drinking water quality directives, will no longer be made systematically and in a way that can be compared with states remaining in the EU.

Summary

In the short term, it is unlikely we will see significant changes to water policy across the UK. However, over the medium-to-long term, there is a risk that current protections may be weakened. New technical standards may not be adopted, especially if they require capital investment. River basin planning may continue, but without the specific time frames or obligations regarding good ecological status from the WFD. Different approaches to ownership of water services may continue, but the future of the differential approach to water resources in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will depend on the governance arrangements for the new UK frameworks. It therefore remains to be seen whether a coherent and well-coordinated water policy survives the on-going political wrangling over post-Brexit environmental policy competence.

Dr Sarah Hendry is an academic lawyer specialising in water and environmental law. She works in the Dundee Law School and the University of Dundee in the Centre for Water Law, Policy and Science.

Photo courtesy of John McSporran.