The environment in the Brexit deal: A brief guide

Tonight, the UK Parliament is scheduled to vote on the Brexit deal which was agreed to in principle by Theresa May’s government and the EU-27 on 25 November 2018.

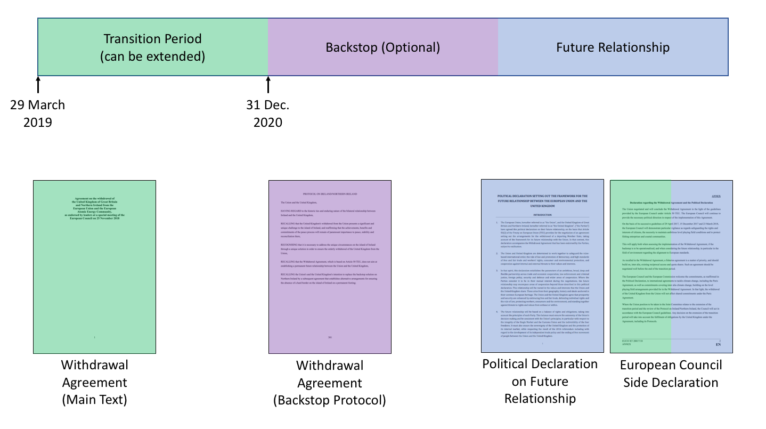

The key components of the deal are the Withdrawal Agreement (including the Ireland/Northern Ireland backstop protocol) the Political Declaration on the Future EU-UK Relationship, and a side declaration from the European Council.

In this blog post, I give an overview of the deal’s components and what they imply for post-Brexit environmental governance (see also early reactions from Prof Colin Reid and Prof Andy Jordan in November 2018).

Overview

The Brexit deal addresses three time periods (see the figure above). The main text of the Withdrawal Agreement addresses the ‘transition/implementation period’ between Brexit Day on 29 March 2019 and 31 December 2020 (there is also an option to extend the transition for one or two years).

The Ireland/Northern Ireland Protocol (the ‘backstop’), as a part of the overall Withdrawal Agreement, addresses what will happen if the EU-UK future relationship is not yet agreed after the end of the transition period. Given the fact that previous EU agreements with third countries have taken years to adopt, it is likely that the backstop will be used. However, both the EU and UK have said they prefer to move immediately to the future relationship.

Finally, the Political Declaration deals with the future relationship, and the European Council side declaration deals with both the transition period and the future relationship.

The Withdrawal Agreement

During the transition period addressed in the main text of the Withdrawal Agreement, EU law – including environmental law – will continue to apply in the UK. This is not a surprise: the EU and UK largely agreed on this text in March 2018.

The Common Agricultural Policy, the Common Fisheries Policy, and the more than 400 existing EU environmental policies will remain in effect. They will be enforced by the EU and the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

Therefore, while ‘environmental policy after Brexit’ is often discussed, if the Withdrawal Agreement is adopted it might be better to think about ‘environmental policy after the transition period’.

The Backstop Protocol

If the UK and EU fail to agree a future relationship by the end of the transition period, then the UK will be subject to the environmental provisions in the backstop protocol.

Under the backstop, the UK and EU commit to common environmental principles. The UK commits to maintaining the same ‘level of environmental protection’ (non-regression) in a wide range of policy areas. In fact, the UK’s non-regression commitments under the backstop are more extensive than those covered by the European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement with Norway (e.g. the EEA countries do not implement the Birds Directive or Habitats Directive, but the non-regression article mentions ‘nature and biodiversity conservation’).

Many of these commitments leave room for divergence between the EU and the UK in exactly how the level of environmental protection is pursued (e.g. though different policy instruments), with three important caveats.

First, Northern Ireland will directly implement a number of EU environmental laws related to avoiding a hard border on the island of Ireland. The CJEU will continue to have jurisdiction over the implementation of these laws in Northern Ireland.

Second, the Joint Committee created to implement the Withdrawal Agreement will directly set minimum commitments for the sulphur content of maritime fuels and pollutants covered by the National Emission Ceilings Directive and the Industrial Emissions Directive.

Third, the UK will commit to an enforcement body (the proposed Office for Environmental Protection) that is transparent, adequately resourced, able to effectively sanction violations of environmental law, and enjoys the power to initiate proceedings and bring legal action. These commitments effectively constrain the UK government’s choices in designing the OEP and unlike the non-regression commitments are eligible to be brought before the Withdrawal Agreement’s dispute mechanism.

The Political Declaration on the Future EU-UK Relationship

The political declaration is aspirational, is not legally binding, and could encompass a wide range of scenarios for the future relationship (from Norway to Canada). However, the declaration and the related European Council statement do make a number of specific statements on environmental policy and governance.

The declaration states that the EU and UK will work together to ensure high environmental standards and discusses continued level playing field commitments on the environment after the backstop ends. It also says the two should ‘consider cooperation’ on carbon pricing if the UK leaves the EU Emissions Trading System.

The European Council’s additional statement, laying out further EU priorities outside the formal documents, states that the Council ‘will demonstrate particular vigilance as regards […] the necessity to maintain ambitious level playing field conditions and to protect fishing enterprises and coastal communities.’

The Council makes clear this vigilance will extend to both the Withdrawal Agreement and the future relationship.

Finally, it states, on climate change, that ‘the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the Union will not affect shared commitments under the Paris Agreement.’

Conclusion

The draft Brexit deal lays out details of the UK’s relationship to EU environmental policy for a number of years to come, if it is adopted.

And it is arguably the only deal – in broad outline – that the EU-27 will agree to with the UK.

So, at least at this juncture, even with the political turmoil in the UK around the meaningful vote, it is indeed likely that it is either this deal, a no-deal Brexit or no Brexit.

Time will tell which one comes to pass.

About the author

Brendan Moore is a Senior Research Associate at the University of East Anglia and the Brexit & Environment network coordinator.

State of the Union – Glasgow University Magazine

12th April 2019 at 8:13 am[…] to international agreements to tackle climate change, including those which implement the United Nations Framework Conventions on Climate Change, such as the Paris […]