The Internal Market Bill: Why negative integration is causing such negative feelings

The UK’s Internal Market Bill, published in early September, has caused a stir right across the UK and in Brussels too. Beyond the critical question of what the Bill means for the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, the Bill also has implications for devolved competences, including over the environment. In an earlier series of posts, we investigated what the original White Paper may imply for these important matters. With the text of the Bill having now been published we can dig further. This post builds on a discussion at a recent Institute for Government roundtable, which you can watch here.

These two issues, devolved competences and the environment, go to the heart of the Internal Market quandary: in what conditions (and to further what policy objectives) should divergence be accepted? The answer to this question will not be the same in different Internal Markets – different markets balance objectives differently, and this also changes over time. Learning from the EU’s own Internal Market (and the large scholarship on it), we can identify two different strategies: what Fritz Scharpf termed ‘positive and negative integration’. Positive integration aims to replace diverging national rules by a single harmonised rule. Negative integration occurs when harmonisation is not politically acceptable – and operates via the mutual recognition of diverging national rules. It removes barrier to trade without the benefit of prior harmonisation – and usually comes with caveats.

The UK Internal Market proposal stands out as relying almost exclusively on negative integration. By doing so, as Prof Michael Dougan argues, ‘it magnify[ies] England’s inherent advantages yet further and risk rendering the exercise of many devolved powers redundant in practice’. One area in which these devolved powers risk becoming redundant is the environment. To understand better how lopsided the UK Bill is, we need first to appreciate how the EU Internal Market accommodates (environmental) divergence.

Balancing positive and negative integration in the EU’s internal market

In the EU’s Internal Market states are protected from downward environmental divergence by their peers. Before harmonisation (i.e. when negative integration is pursued), states can curtail mutual recognition obligations if non-domestic products undercut key standards that are objectively justified. Once harmonisation is achieved downward divergence is prohibited. Conversely, the scope for upward divergence differs widely.

When it comes to the environment in the EU internal market, positive integration is further divided into two categories: one directly impacting the internal market (such as product standards); another that has a less constraining effect on the internal market (process standards, nature protection…). These two categories of EU environmental law are agreed under two different legal bases (that is, different articles of the EU Treaties). And with these two legal bases come varying possibilities to diverge upward.

Environmental policies on water, air or nature are considered as having little impact on the internal market – they are agreed under the Environment Title of the EU Treaty (article 192 TFEU), and EU rules adopted create a minimum baseline Member States can go beyond (as long as upward divergence is proportionate to meet objective policy aims).

Conversely, environmental policies on packaging waste, chemicals or GMOs are agreed under the Approximation of Law Title of the EU Treaty (article 114 TFEU). there, Member States’ potential to diverge from harmonised policies is much more limited (higher national standards, new science-based issues specific to a country….).

Which legal basis is used for EU environmental policy can be deeply contested and is not always clear cut: thus, the 2015 directive on reducing the use of plastic bags was agreed under article 114, while the 2019 directive on reducing single use plastics was agreed under article 192.

As for negative integration, mutual recognition is not absolute in the EU internal market. Exemptions to this principle can be found in the Lisbon Treaty (article 36 TFEU) – which includes a narrow environmental purpose (‘the protection of health and life of humans, animals or plants’) and in European Court of Justice case law which has reiterated that protecting the environment is a mandatory requirement in the EU treaties, and that, in the absence of harmonisation, environmental exemptions to mutual recognition can be acceptable (as long as they are proportionate, etc.).

Negative integration only in the UK Internal Market?

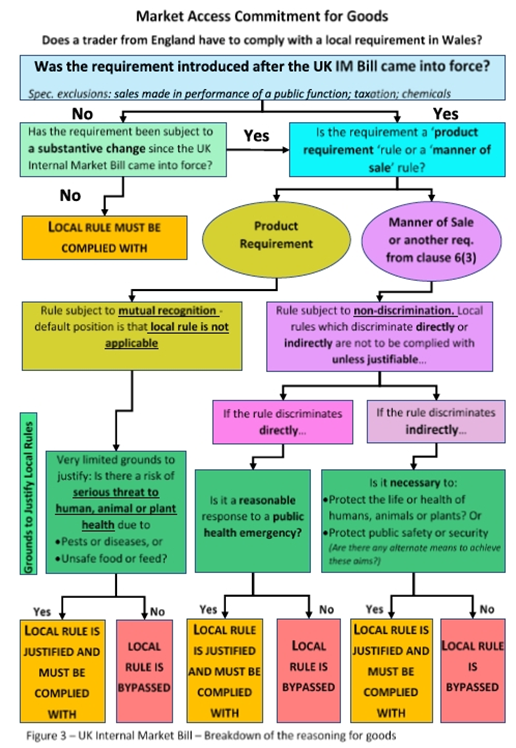

By contrast, the UK Government’s internal market Bill pursues a different approach to the EU’s Internal Market. The onus of the Bill is not on fostering positive integration – which, in the UK’s preparation for Brexit, has been pursued under the Common Frameworks mechanisms. Crucially, Common Frameworks are not mentioned in the Bill. Instead, the focus is on negative integration, based on mutual recognition and non-discrimination. The Wales Centre for Governance has put together a very helpful graph to understand how exemptions to the principles would work (see below).

Pre-existing rules will continue to apply. But once there are substantive changes, the UK Internal Market principles kick in. If regulatory change concerns a product requirement (packaging, ingredient, labelling…), then mutual recognition applies. If it’s a ‘manner of sale’ requirement (licensing, transportation, advertising…), then non-discrimination kicks in.

By contrast with the EU, pursuing environmental aims (even widely defined) are not a valid exemption from Mutual Recognition in the Bill – only in so far as preventing pests or diseases. Environmental exemptions are more fleshed out in cases of discrimination but only if they are indirect. More importantly, there is no ban on downward divergence, i.e. environmental dumping. Thus, the devolved administrations may win some limited new powers to diverge – introducing either higher or lower standards for goods produced in their territory – but they also lose the critical power to protect their markets against products – perhaps originating from outside the EU – which do not meet their preferred minimum levels of environmental protection.

The fact that pre-existing rules, even if already diverging, remain in place is reassuring in the short term, but not in the medium or long term. Take for example GMOs and gene editing. Currently, the devolved’s bans are bans on a specific type of GMOs, and new strands or technologies, if accepted via UK trade deals, could not be banned from being sold on devolved markets. Devolved powers over GMOs are protected by a Concordat between the four nations – but this can be terminated by any of them with a six months’ notice.

This focus on protecting existing rules may also have, as Greener UK argues, a ‘chilling effect’ on upward divergence. If the only way to prevent market access for products undercutting standards is to maintain the regulatory status quo, administrations will think twice before substantially changing rules to increase standards. Not only would such an increase solely apply to domestic producers, but it also opens the door to products both from the rest of the UK and the world which could undercut previous standards.

Figure 1. Building an Internal Market for the four nations

Unsurprisingly, the Bill, whose own impact assessment states that ‘in certain instances, where parts of the UK pursue separate policies, the scale of the intended public benefit of local measures might not be fully realised due to the more limited number of goods and services to which the policy applies’, is deeply unpopular with the devolved administrations. What can be changed to address their concerns?

The Bill’s focus on negative integration is, unsurprisingly, driving negative feelings. Instead of a UK Internal Market built with the devolved administrations, the Bill puts forward an Internal Market proposal done to them. This focus on negative integration further means that a key distinction in EU law – between policy directly impacting the internal market where upward divergence is limited, and more general environmental policy where upward divergence is less constrained – is missing.

Firstly, the Bill needs to bring positive integration back in. In some areas, the four nations may be willing to trade limited powers to pursue upward divergence for protection against downward divergence (both from within the UK and from imports). This could be achieved through positive integration, via the Common Frameworks process which needs to be looped into the Internal Market discussions. Thus, for example, mutual recognition could be limited to cases where a common framework is not agreed. This would create an incentive for the UK administrations to cooperate. While England, as the largest market, may benefit the most from an approach focused on negative integration, it may be politically difficult for Westminster to be seen to be refusing UK-wide solutions.

Second, the Bill needs to recognise the existence of other valid policy objectives. Limiting barriers to internal UK trade need not be the only, nor necessarily the overarching policy objective. As in the EU context safeguards need to be put in place, and not just for the “serious threats to human, animal or plant health”. This should be done both in the Bill, setting out how other policy objectives can be balanced against removing barriers (drawing on the principle of proportionality, establishing a list of acceptable justifications etc.), and in the Environment Bill which needs to be returned as soon as possible to the House of Commons.

About the author

Dr Viviane Gravey is a Lecturer in European Politics at Queen’s University

Belfast and Co-chair of the Brexit & Environment network.

Picture courtesy of JerzyGorecki|pixabay