Towards an Ever Closer Union?

The slogan “taking back control” always begged the question of who would eventually wield such control: – central government in London or the devolved administrations? The UK Internal Market White Paper attempts to provide answers to this question, and the answers, as sketched out in this blog, that are unlikely to find much favour with the devolved administrations.

Its publication also powerfully reminds us that the ongoing UK-EU negotiations are not the only part of the Brexit process which will impact the environment. Intergovernmental negotiations within the UK will eventually play a big, if not a bigger role in determining how Brexit affects environmental quality and thus the daily lives of every UK citizen.

Competences: who will do what?

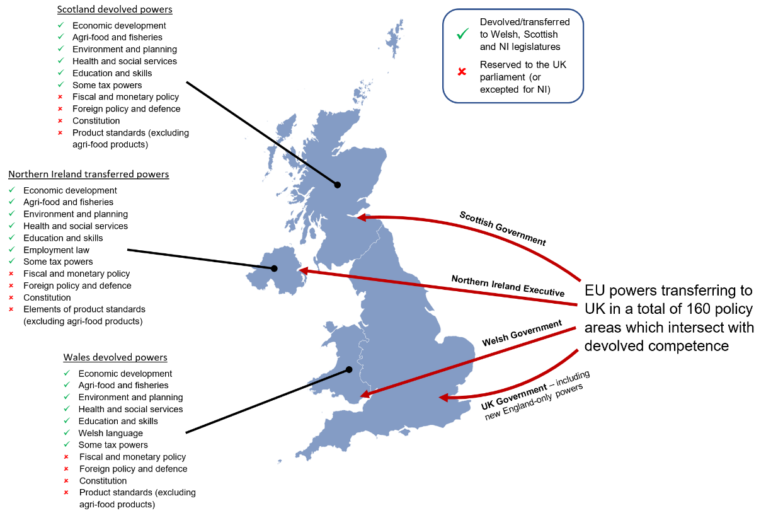

Some of the policy making competences coming back are clearly reserved to the UK government, whereas others were already devolved. Yet even with clear-cut allocations, interactions need to be considered: reserved competences can constrain the exercise of devolved competences, and vice-versa. Thus, for example, let’s consider the oft-debated issue of chlorinated chickens and future trade deals. Reserved competence in negotiating trade deals may be affected by continued opposition to accepting the commercialisation of chlorinated chickens in the devolved parts of the UK. Conversely, if the UK government were to sign a trade deal allowing such commercialisation, it could constrain devolved competences on animal welfare and product labelling etc. as they are bound to implement international obligations. Sorting through these competences, and deciding whether and how much GB-wide or UK-wide cooperation is needed in areas of devolved competence is an on-going process. For the last few years, this has focused on debating ‘common frameworks’, i.e. looking at specific policy areas individually, deciding between the four administrations whether political, legal or no UK-wide frameworks were needed. The White Paper goes a step further – it tries to address the overarching structure, the institutional glue holding all these policies together, accounting for interactions and spill-overs from one policy area to the next.

Key principles of the UK Internal Market proposal

Changes to the UK Internal Market subsequent to devolution in the late 1990s were accommodated through the rules and governance structures of the EU Internal Market. A clear set of legally binding rules enforcing a level playing field between Member States (which now find themselves central to UK-EU negotiations), overseen by the Court of Justice of the EU. Considering the various post-Brexit options, academics have sketched out four options ranging from a UK-wide piece of legislation providing a general structure (1), to a new UK-wide body providing regulatory oversight (2), to policy-specific frameworks (3), down to no supervision at all (4).

Options 1 and 2 protect UK reserved competences and limit regulatory divergence the most, while options at 3 and 4 allow much greater regulatory divergence in areas of devolved competences. As such, they are much more likely to get support from the devolved administrations. Unsurprisingly, the approach chosen by central UK government favours Option 1, the most centralized, with some limited elements of 2 and 3. This is justified in the White Paper as the best way to provide regulatory certainty, and simplicity.

The White Paper published on 16 July sets out structure for the UK Internal Market relying on two key principles, mutual recognition and non-discrimination. Mutual recognition means that goods produced to Welsh requirements can be sold in English shops and vice-versa. Some policies will be outside the scope of the principle (“exclusions”) – the White Paper gives some examples: “taxation and spending, existing reserved areas, or social policies with little Internal Market impact”.

Non-discrimination means that an “authority must regulate in a way that avoids differential and unfavourable treatment to goods or services originating in another part of the UK to that afforded to its own goods or services.” This second principle also comes with some exceptions, although these appear much narrower (but with no exhaustive list either): “The non-discrimination principle will allow scope for such differential treatment where this is necessary, for example, to address a public, plant or animal health emergency”. The White Paper explains how these are principles commonly govern internal markets. Indeed, they underpin the EU’s own Internal Market.

EU and UK Internal Markets: three crucial differences

Reading through the White Paper it is remarkable how it uses EU terms and concepts – non-discrimination, mutual recognition, spill-over etc. Yet there are three profound differences between these two Internal Markets. First, there is the matter of power balance and market size. No single EU member state can change EU rules. In the UK system, Westminster represents both England and the UK as a whole – indeed, Prime Minister Johnson’s majority is such that new rules could be adopted by English MPs. England’s economy dwarves the rest of the UK – this means that, in practice, and indeed in most examples in the White Paper, divergence in the UK context is not understood as four nations diverging from one common, UK wide rule, but as one of the devolved administrations diverging from the UK (England) norm.

Second, while both markets use legally-binding principles, the EU cannot expand its competences without Member States deciding to grant it greater powers – and their own powers are protected in legally binding treaties. The White Paper puts forward legally-binding constraints on devolved competences even though the devolved administrations’ right to withhold consent to the UK’s Parliament legislating in devolved matters (the Sewel Convention) was found to be not legally binding.

Third, the principles have different, and wider, caveats in the EU market. For instance, Member States are expressly allowed to set their own rules going beyond harmonized rules “relating to the protection of the environment or the working environment” (Article 114 TFEU).

What about Northern Ireland?

For a White Paper which speaks at length of the “hassle” of regulatory divergence for businesses, stressing how “businesses need certainty and clarity to operate smoothly across the UK” it spends little time discussing the situation in Northern Ireland, specifically what the NI Protocol means for UK Internal Market plans. As Hayward argues, “the biggest challenge to the coherence of the UK internal market arises from what the Protocol means for goods crossing from GB into NI.” If there is divergence between rules in GB and in the European Union, certain GB goods will not be accepted in NI.

What does this mean in terms of mutual recognition and non-discrimination? In a deregulatory scenario, in which English rules on e.g. requirement GMO labelling were to be cut, English labelling will have to be accepted in Welsh and Scottish shops – under the mutual recognition principle. This would make it difficult in practice for Welsh and Scottish authorities to continue a different labelling scheme. But NI would be in a very different position. While the mutual recognition principle would apply NI to GB (NI goods would be accepted on GB markets), it will be trumped by NI Protocol rules for GB to NI trade. If GB goods do not comply with relevant EU rules, they won’t be able to be put on the NI market, mutual recognition notwithstanding. As the smallest of the four UK markets, it would make little sense for retailers (unless they were also for example, selling into the Irish market too) to run different production lines for GB and NI. In practice this would lead to smaller choice available in NI, and likely higher prices.

As for non-discrimination, while commitments to apply non-discrimination to NI goods and services are welcome, how this will work is not yet clear. Furthermore, if England were to cut its standards in any area in which NI producers would still be bound by EU rules, they may not be discriminated against but they will likely lose market shares as too expensive.

In conclusion, the proposed Internal Market is likely to stifle policy divergence and innovation from the devolved administrations – but it will have a different impact across the UK. While considerable differences in market size mean that Welsh and Scottish rules may have to align themselves in practice with English rules (or face important political and economic costs), NI rules will not be able to follow in areas governed by the Protocol. Under the guise of limiting intra-UK divergence, the White Paper instead limits intra-GB divergence, and furthers the likelihood of deeper regulatory divergence across the Irish sea.

About the authors

Dr Viviane Gravey is a Lecturer in European Politics at Queen’s University

Belfast and Co-chair of the Brexit & Environment network. Andy Jordan is Professor of Environmental Sciences at the University of East Anglia.

Image from the Government’s UK Internal Market White Paper